History of Har Hazeitim

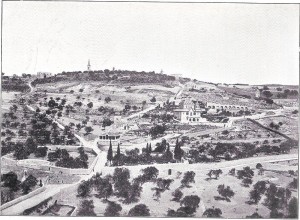

From Biblical times until today, Jews have been buried on Har HaZeitim — the Mount of Olives. The necropolis on the southern ridge, the location of the modern village of Silwan, was the burial place of the city’s most important citizens in the period of the Biblical kings. There are an estimated 150,000 graves on the Mount, including tombs traditionally associated with Zechariah and Avshalom (Absalom). Rabbi Chaim ibn Attar, author of Ohr Hachaim Hakadosh, is also buried there. Important rabbis from the 15th to the 20th centuries are buried there, among them Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel, and his son Zvi Yehuda Kook.

From Biblical times until today, Jews have been buried on Har HaZeitim — the Mount of Olives. The necropolis on the southern ridge, the location of the modern village of Silwan, was the burial place of the city’s most important citizens in the period of the Biblical kings. There are an estimated 150,000 graves on the Mount, including tombs traditionally associated with Zechariah and Avshalom (Absalom). Rabbi Chaim ibn Attar, author of Ohr Hachaim Hakadosh, is also buried there. Important rabbis from the 15th to the 20th centuries are buried there, among them Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel, and his son Zvi Yehuda Kook.

During the Islamization of Jerusalem under Jordanian occupation form 1948 to 1967, Jewish burials were halted, massive vandalism took place, and 40,000 of the 50,000 graves were desecrated. King Hussein permitted the construction of the Intercontinental Hotel at the summit of the Mount of Olives together with a road that cut through the cemetery which destroyed hundreds of Jewish graves, some from the First Temple Period. After the Six-Day War, restoration work began, and the cemetery was re-opened for burials.

Roman soldiers from the 10th Legion camped on the Mount during the Siege of Jerusalem in the year 70 CE. The religious ceremony marking the start of a new month was held on the Mount of Olives in the days of the Second Temple.[11] After the destruction of the Temple, Jews celebrated the festival of Sukkot on the Mount of Olives. They made pilgrimages to the Mount of Olives because it was 80 meters higher than the Temple Mount and offered a panoramic view of the Temple site. It became a traditional place for lamenting the Temple’s destruction, especially on Tisha B’Av. In 1481, an Italian Jewish pilgrim, Rabbi Meshulam Da Volterra, wrote: “And all the community of Jews, every year, goes up to Mount Zion on the day of Tisha B’Av to fast and mourn, and from there they move down along Yoshafat Valley and up to Mount of Olives. From there they see the whole Temple (the Temple Mount) and there they weep and lament the destruction of this House.” In the mid-1850s, the villagers of Silwan were paid £100 annually by the Jews in an effort to prevent the desecration of graves on the mount.

Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin asked to be buried on the Mount of Olives near the grave of Etzel member Meir Feinstein, rather than Mount Herzl national cemetery.

Biblical References

The Mount of Olives is first mentioned in connection with David’s flight from Absalom (II Samuel 15:30): “And David went up by the ascent of the Mount of Olives, and wept as he went up.” The ascent was probably east of the City of David, near the village of Silwan.[1] The sacred character of the mount is alluded to in the Ezekiel (11:23): “And the glory of the Lord went up from the midst of the city, and stood upon the mountain which is on the east side of the city.”[1] Solomon built altars to the gods of his wives on the southern peak (I Kings 11:7-8). During the reign of King Josiah, the mount was called the Mount of Corruption (II Kings 23:13). An apocalyptic prophecy in the Book of Zechariah states that Yahweh will stand on the Mount of Olives and the mountain will split in two, with one half shifting north and one half shifting south (Zechariah 14:4).

The biblical designation Har HaMashchit derives from the idol worship there, begun by King Solomon’s Moabite and Ammonite wives “on the mountain which is before (east of) Jerusalem” (Kings I 11:17), just outside the limits of the holy city. This site was infamous for idol worship throughout the First Temple period, until king of Judah Josiah finally destroyed “the high places that were before Jerusalem, to the right of Har HaMashchit,…”

Jordanian Occupation (1948–1967)

In the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Jordan occupied East Jerusalem, including the Mount of Olives, and held it until the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. During this period, Jordan annexed its part of the city, but this was recognized only by the United Kingdom and Pakistan. Jordan had obligated itself within the framework of the 3 April 1949 Armistice Agreement to allow “free access to the holy sites and cultural institutions and use of the cemeteries on the Mount of Olives,” but it did not honor this obligation.

By the end of 1949, and throughout the Jordanian occupation of the site, Arab residents uprooted tombstones and plowed the land in the cemeteries, while skeletons and bones were strewn about and scattered. An estimated 38,000 tombstones were smashed or damaged in total. Jewish tombstones from the Mount, both ancient and new, were used by the Jordanians for various purposes, including flooring for latrines and paving stones for roads. During this period, four roads were paved through the cemeteries, in the process destroying graves including those of famous persons. Buildings, including the Intercontinental Hotel and a gas station, were erected on top of ancient graves.